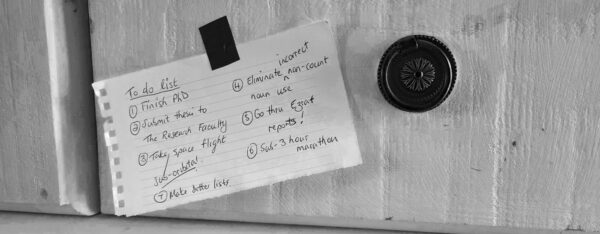

Can you imagine an research report without a list, whether in-line, bulleted, or numbered, or in a table? Most unlikely. Even this article started with a list. To improve your academic and business writing, a good start is sharpening your list-making skills.

1. The last item

As well as

Academic writers should be succinct, clear, and unambiguous, as well as avoiding jargon.

What is wrong with this sentence? The unnecessary wordiness of as well as! Do not use as well as when and will do. I had one client who ended every list with as well as. I asked her why she did this and her response was that, to her, it sounded better. Imagine my astonishment!

First, the phrase is wordy and wordiness always weakens readability. Second, she committed the error of repeating the form, without variation, over and over.

Never use as well as when and will do. You should only use as well as when your last item differs in quality or character from the preceding items and you wish to maintain the distinction. Thus, you might write:

✓ Academic writers should be succinct, clear, unambiguous, and avoid jargon, as well being capable of long stretches of concentration.

This is okay, because the first four items in the list describe the quality of the writing, while the last is about the process.

Missing and preceding the last item

The last item in a list should be preceded by and. Thus not:

🗴 … be succinct, clear, unambiguous, avoid jargon.

But rather:

✓ … be succinct, clear, unambiguous, and avoid jargon.

This error is often seen in as well as lists. Thus, in error:

🗴 … be succinct, clear, unambiguous, avoid jargon, as well being capable of long stretches of concentration.

2. Three-item compulsion

I had one client who apparently thought that turning any given concept into a list of three looked clever. One example:

🗴 An intervention should be established to address socio-economic inequality, differential levels of poverty and poor service delivery.

Is there a meaningful difference between socio-economic inequality and differential levels of poverty? No; but this writer wanted a three-item list (I presume).

The solution? Accept that expanding one item to three may, on the surface, sound more academic, but in practice makes for tedious reading.

3. Incorrect latter

If your list has three or more items, you cannot use latter. The word latter means the second of two items. It does not mean the last item in a list. When the list has more than two items, write something like:

✓ Academic writers should be succinct, clear, and unambiguous. The last of these is particularly important.

4. Choosing a list format

In-line numbered lists

✓ Academic writers should be (a) succinct, (b) clear, (c) unambiguous, and (d) avoid jargon.

In-line numbered lists, like the one above, are underutilised. This is a pity because they are easily readable and can add variety to list forms. Apply the principles of (1) separating the items with punctuation, such as a comma, (2) using lower case letters for the start of each item, and (3) inserting and before the last item.

Bulleted lists

For bulleted or numbered lists, few hard-and-fast rules apply, but useful guidelines include:

- Aim for consistency of style, formatting, and punctuation

- Avoid lists of only two or three items, especially if the bullet points are just one or two words long

- Avoid more than one complete sentence within a single bullet point

- Use the same grammatical form for each bulleted point

Regarding the last point (not the latter point!), here is an example of mixed grammatical forms:

- Omit needless words

- Avoid jargon intended to make you look clever

- Explaining acronyms on first use

The first two points use the imperative form of the verb (omit and avoid); the last uses a past participle (explaining). This should be written as (with the revision highlighted):

- Omit needless words

- Avoid jargon intended to make you look clever

- Explain acronyms on first use

Numbered lists

Use numbered lists, not bulleted lists, when the quantity or rank order of items is significant. In our example, you could use bullets, but if wanted to emphasise that writers need to address four aspects of writing and not some other number, you could write:

Academic writers need master just four principles:

- Be succinct

- Be clear

- Be unambiguous

- Avoid jargon

Tabulated lists

Bear in mind the option of turning your list into a table. If your list is complex, you probably should tabulate. On the other hand, your list may be too simple to be tabulated. If so, often you can add content that makes the list worth tabulating. Consider our example:

✓ Academic writers should be (a) succinct, (b) clear, (c) unambiguous, and (d) avoid jargon.

This is too simple to tabulate, but if you added a category and an example you may have a useful table. You may also be able to add rows. Perhaps:

| Severity | Category | Principle | Example |

| High | Clarity | Avoid ambiguity | ╳ He took Fido for active dog training [is the training active or are the dogs active]? |

| High | Academic style | Adhere to style guides | Styles guides include APA, MLA, and Harvard. |

| Medium | Wordiness | Be succinct | In this particular case … |

| Medium | Clarity | Be clear | This is unacceptable [where the referent for This is not clear]. |

| Low | Academic style | Avoid jargon | Her chosen coffee modality was a mug not a cup. |

5. Commas and semicolons

Today the comma is favoured over the semicolon as a list-item separator. Thus, write:

✓ Academic writers should be succinct, clear, unambiguous, and avoid jargon.

However, use semicolons when your items need commas, as in:

✓ Academic writers should be succinct, which means brief and to-the-point; clear; unambiguous; and avoid jargon, which is terminology that is unnecessarily technical or arcane.

Note how semicolons separate the list items and commas separate clauses within the items.

About The Author: Bruce Conradie

Research support specialist and document editor.

More posts by Bruce Conradie